Singing Alexander’s Song: Part 1

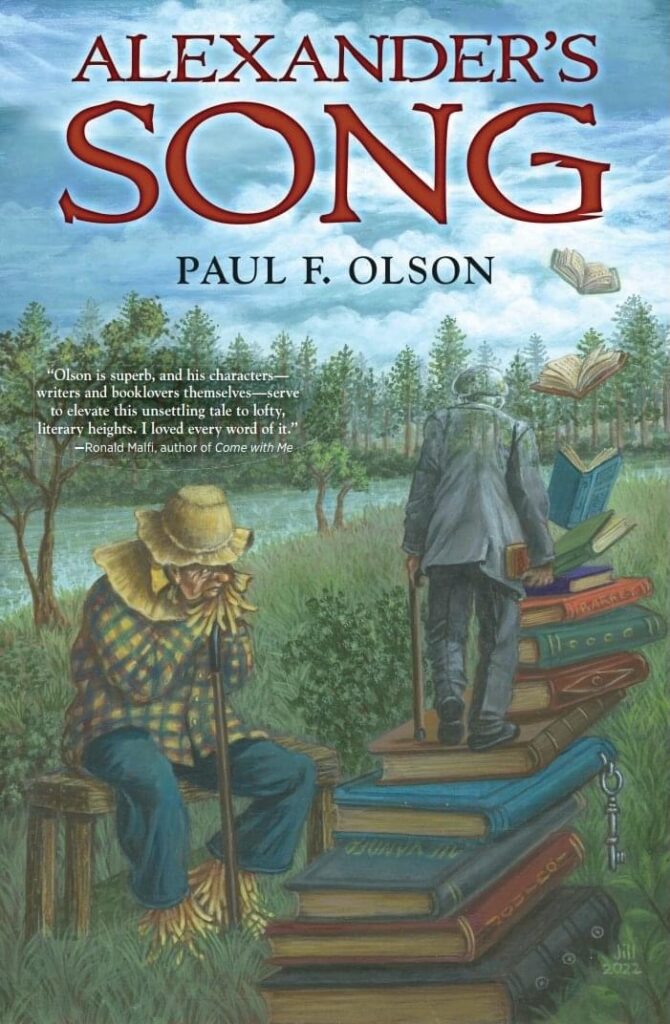

On September 30, 2022, Cemetery Dance Publications will release a brand new edition of my dark suspense novel, Alexander’s Song, in e-book and, for the first time ever, in trade paperback. In preparation, I’m writing a three-part blog post about the book. This is part one. -PFO

Writers get a lot of advice. Most of it — all those dusty old rules beginning with “always” or “never” — should be listened to politely, acknowledged with a smile, and then promptly thrown out the nearest window. But some bits of writing advice are actually worthwhile. Here’s one of my favorites: “Write the kind of story you want to read.” My dark suspense novel Alexander’s Song, about to be published by Cemetery Dance, is a good example of that rule.

“Write the kind of story you want to read” sounds like a fairly straightforward edict, the kind of advice so obvious it scarcely needs to be uttered. But of course all sorts of writers choose not to follow it, for all sorts of reasons. Perhaps they’ve been writing one type of thing for many years and simply continue to write it due to inertia, comfort, or commercial necessity, even as they yearn to move on and try something new. Maybe they’re ghostwriting or doing some other type of work for hire. Or maybe they’re just tired of scrounging for loose nickels in the couch cushions and make the entirely rational decision that it’s time to write to the market — in other words, write the kind of book that’s currently popular — and earn some real money for a change.

These sorts of things were on my mind a lot way back at the dawn of the 1990s when I sat down and wrote the first draft of Alexander’s Song. It was an odd time for me. I was feeling restless, edgy. On the surface, that was ridiculous. After all, I’d been riding a rising professional wave for the previous five years or so, with a satisfying string of short story sales, a successful stint as a magazine publisher, the sale of my first novel, and the publication of two well-received anthologies. I was doing what I’d always wanted to do. I was making money at it. Why in the world would I be feeling so uneasy?

Well, for starters, after publishing my first novel, a vampire tale called The Night Prophets, New American Library had recently rejected my next submission. Looking back, I can honestly say they made the right choice. The book, Eagleton Point, wasn’t very good — a garden variety alien invasion story that I wrote hastily in an attempt to strike while the publishing iron was hot. It lacked several key ingredients, not least of which was the emotional investment of the author, and NAL did all of us a favor by politely turning it down. But I wasn’t quite so calmly philosophical at the time. In fact, I saw the rejection as a troubling omen, indicative of my larger fear that the horror field was changing around me, evolving in a direction that was going to quickly leave me behind, no longer hospitable to the sort of traditional quiet horror that I preferred to read and write.

I was also undergoing a bit of evolution myself. It probably began back when I was whipping up my alien invasion, but I didn’t recognize it at the time. In fact, I didn’t realize what was happening until I took note one day of the kinds of books I was reading. More and more often, you see, I was opting for novels that were large and dense and … let’s say ambitiously complex. I’d always enjoyed that sort of book, the kind of book you can get lost in for long stretches of time, for days or even weeks on end. But on that long-ago day, I suddenly realized that I was no longer just grabbing those books when I happened across them but actively seeking them out, choosing them to the exclusion of other works.

Don’t get me wrong. I’ve got nothing against rip-roaring yarns, those books that take off like a rocket with the first line and drag you helplessly along through a few hundred pages of breathless action. I’ve read literally hundreds of them. Some of my favorite authors are masters of the form. But what I was drawn to back then was something else altogether. I found myself craving novels rich with depth and detail, background and color, plots that were long and involved, usually complicated, often circuitous, sometimes convoluted, books where you might have to come up for air once in a while to remind yourself that the real world still existed, where you might struggle to keep up with the author, where you might even be tempted to jot down some notes from time to time, just to be sure you were really following what was going on. And something else, too. The books I was reading seemed to have a total disregard for genre. They were, for want of a better term, genre-fluid, ignoring the standard conventions and moving deftly back and forth between mainstream, adventure, suspense, horror, mystery, and often a few other things to boot.

That’s when it dawned on me, with all the subtlety of a piano falling from a tenth-story window and landing on my head. This was what I wanted to do. This was the kind of book I wanted to write. No. Needed to write. And in that spirit I went down to the dingy basement office of our tiny house in Wheaton, Illinois, fired up my computer, and typed “On a warm, windy Friday in late April, a thirty-year-old schoolteacher named Andy Gillespie looked down on Rock Creek, Michigan,” launching myself headlong into the story that would become Alexander’s Song. I wasn’t thinking of that weary old truism “Write the kind of story you want to read,” but of course that was exactly what I was doing.

Once I started, I never looked back. If part of the problem with the rejected Eagleton Point was that I never gave my entire heart and soul to the project, I was fixing that problem this time around in bold, dramatic fashion. A few months later, I was several hundred pages into the novel, happily lost in a plot that seemed to grow darker and more complicated with every passing paragraph. I still didn’t know the entire story. I had a famous author with a mysterious past and a number of ominous developments, but also lots of unanswered questions, missing links, loose threads, and black holes. Nevertheless, I had that weird, adrenaline-fueled overconfidence that is the hallmark of an author on a roll. I was sure that everything would come together in the end, and in the meantime, I was sure as hell enjoying the ride.

That’s when my agent called.

She was going to be passing through the Midwest and wanted to meet. We ended up having a lovely Sunday brunch at Chicago’s iconic Drake Hotel, where we talked business and gossiped for several hours. Then she asked what I was working on. I told her about Alexander’s Song, enthusiastically describing what I knew of the plot so far and where I thought it might be going. I was about to add that I thought the novel might just end up being my breakthrough book, the one that catapulted me beyond the horror midlist into the wider, brighter world of mainstream notice and commercial success. But as I opened my mouth to say those things, I saw the expression on her face and stopped. Was she looking at me with profound disappointment? That’s certainly the way I interpreted it. And I realized that we were going to be having a completely different sort of conversation than the one I’d envisioned.

She talked for a bit about the realities of publishing, about my first two novels, about expectations for the next one, and about the need to stay focused if I was going to build a career as a horror writer. And then she said something I’ve never forgotten.

“You’re at the point where you have to make a decision,” she told me. “You have to decide if you’re going to write for artistic satisfaction or if you want to make money and have a career.”

We finished the brunch and parted amicably, but I sensed that something fundamental had changed between us. Perhaps it had changed inside me as well. On the drive back to Wheaton, I thought about what she had said. I decided she was right. I decided she was wrong. I decided that I cared a great deal. I decided that I didn’t care at all.

When I got home, I went to the basement and jumped with great relief back into the world of Alexander’s Song. The mysteries were still waiting to be solved, and that task happily absorbed me for the next six months or so. I’m sure there were times I fretted about that phrase — artistic satisfaction — just as there were times I thought I might be better off writing another vampire book or trying to fix the problems with my rejected alien novel or putting my efforts into joining the burgeoning splatterpunk revolution. But mostly I was happy right where I was. I was writing the kind of story I wanted to read, and for the moment, that was more than enough.

Next time: Solving the mysteries, finishing the book